Lesson 1 - An Introduction to the Stock Market

(To obtain this as a PDF document click here)

As mentioned in ‘Getting Started’, most people think that the Stock Exchange has nothing to do with them. However, this is not the case since most people have an insurance policy, pay pension or provident-fund contributions, buy unit trusts, or just put your money in a savings account, it matters a great deal. This is because the administrators who collect your money, invest it in shares listed on the stock market. You are now taking the first step towards directly investing your money in the stock exchange. Before you join the millions of others who invest directly, let's look at what the Stock Exchange is all about.

When a company needs funds, it could go to a bank and ask for a loan. However, as we will discuss later, it is more sensible for a company to go to a stock exchange and asks the public for the necessary money. Effectively, the owner of the company sells part of the company to the investors. The company is not broken up into bits and sold, but rather it’s original operation is retained, and shares in the company are sold to investors.

A stock exchange is a place to buy and sell shares: it is a market. A share is just what it says it is - a share or slice or piece of a company (A share certificate is a piece of paper that indicates what portion of the company the holder of that certificate owns.). Buy a share and you become a co-owner of the company. You share in its profits if it pays a dividend, and you undoubtedly share in its broader future: the share price will rise if the company does well and your share will be worth more. You can sell it for a profit, or use it as collateral against a bank loan if you do not want to sell. Nevertheless, if your company does badly, its share price will fall and you will lose some of your capital investment. That’s the risk.

Usually the shareholders of a company have no say regarding the day to day running of the company. The company’s directors decide how much of the company’s profits should be retained to fund future growth and how much should be paid to the shareholders who provided the capital in the first place. This they declare as a dividend.

Stock Exchanges started way back in 1602 when the Dutch East India Company (VOC) started. The London Stock Exchange (LSE) was formed in 1801. Just a decade earlier the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) traces its origins to an agreement set up by 24 American brokers.

In South Africa, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) which was founded in 1887 out of necessity, and not simply out of a desire to have a South African stock exchange. It was established by an act of Parliament, called the Stock Exchange Control Act. The act provides for the internal monitoring of all activities by a committee.

At that stage in history, gold-mining fever had gripped the country and miners needed capital for equipment to expand and continue operations. The stock exchange provided the companies with a marketplace to raise the necessary capital to continue mining. This is the concept of all stock exchanges - a place where business operations can raise capital to start or continue their operations.

Usually only a locally registered stockbroker can buy and sell shares for you on the exchange of any given country.

He charges a fee called commission or brokerage for this service.

This fee is negotiable and you should shop around and talk to several brokers before choosing one for yourself.

The Exchange itself will have a public relations department or a website that will provide you with the names and contact details of all stockbrokers.

This and other related information is listed on many sites on the Internet.

The stockbroker that you choose will open an account in your name.

You will be able to get investment advice from them although the ultimate decision to buy or sell is yours.

When you ask a stockbroker to buy shares for you they can do it in one of two ways. They can either act as an agent or a principal. When acting as an agent the stockbroker will purchase the shares that you have asked for by notifying other stockbrokers that you are looking for those shares. However, when the stockbroker is acting as a principal they will sell you shares that they already hold in the stockbroking firm’s account and hence are not allowed to charge you brokerage fees.

Although there is no restriction as to how many shares one can buy or sell, stock brokers like to deal in lots of 100. You become the owner as soon as the deal is concluded and will receive a broker’s note to confirm the transaction a few days later.

The broker’s note is important, as it shows details of the deal and all of the charges that you are liable for. The share certificate, your proof of ownership, arrives later, and needs to be kept in a safe place. If you lose it you will be charged a replacement fee. You must produce it when you sell the shares. Your broker will, for a small fee, keep it in safe custody for you if you wish. The JSE is moving away from issuing share certificates as they are vulnerable to fraud.

You used to pay for the shares within seven business days of buying them, however, most brokers now insist on having the money in your account with them before they will purchase shares for you. Besides the cost of the shares, there is a brokerage charge and then local tax (VAT/GST/etc.) on the brokerage only. If you are purchasing shares, there is also a stamp duty called marketable securities tax (MST), of 0,25% of the value of the purchase.

Suppose you hold 100 shares in a big chain store. Because you have to buy a new car or pay heavy medical expenses, you decide to sell these shares. You approach your stockbroker and give him instructions about how many you wish to sell and at what price you wish them to be sold at. There are nearly always buyers for shares in the marketplace according to the laws of supply and demand. The stockbroker endeavours to sell your shares by listing them for sale at a price you have specified on the JSE’s computer system. The computer will match and conclude a transaction as soon as it receives a request for your shares from another stockbroker who has a client who is prepared to buy your shares at the price you have specified. The stock exchange is merely a marketplace where buyers and sellers can be brought together to exchange their shares at prices determined by free competition.

Even if you have never owned shares, you are probably an indirect investor on the stock exchange. You might have an insurance policy or money in a bank or deposit account or you might pay into a pension or provident fund. All these organisations use the stock exchange to invest some of the savings you contribute.

If you can’t afford to invest on the JSE on your own but you’d like to own shares then you should consider joining an investment club. Such a club can be formed with friends or colleagues and once you have formed such a club you can appoint a stockbroker to manage your business. By each contributing a fixed amount each month and depositing it into a special account, you will have a more respectable amount of money to invest on the stock market.

For a clearer understanding of a stock market it might be helpful to imagine that you own a small business but would like to expand. What do you need before anything else? Capital.

You need money for buildings, plant and materials, for wages and salaries; for all the expenses that must be met before the new project can pay its way.

Perhaps you have enough money yourself to finance the enterprise; but if you are starting a large business you will undoubtedly need considerable sums that you probably cannot raise on your own.

To meet such needs, joint stock companies came into being. Through them many people club together to subscribe the capital - which is divided into shares - for enterprises that are too large financially for individuals to handle. Investment in stock and shares gives you a part ownership of the company whose shares you buy. If you buy ordinary shares, you own part of the land, factories, machinery and plant of the company, in which you invest. As the value of money decreases - as it continues to do these days - so the value of these assets and your small share of them increases.

If before World War II a company made shoes and sold them at say 300 a pair, of which say 20 percent (60) was the profit, it would probably now be selling shoes at 13,500 a pair, still making 20 percent profit (2,700). In a well-managed company the output would probably have increased and the profit would be much more than eight times its value before the war. Obviously, the dividends paid would also have increased proportionately. This example is an oversimplification but it serves to show that investment in ordinary shares is one way of ensuring against falls in the purchasing power of money. Suffice it to say, it has been proven statistically that the return on share investments has consistently outperformed other investments such as property, cash deposits, etc. over extended periods.

If you deposit your savings with financial institutions, which pay you a fixed rate of interest on your money and undertake to return the capital amount when you want it, that money is lent at a profit by the institutions to others, for example, to buy property or houses, or finance a business through a loan.

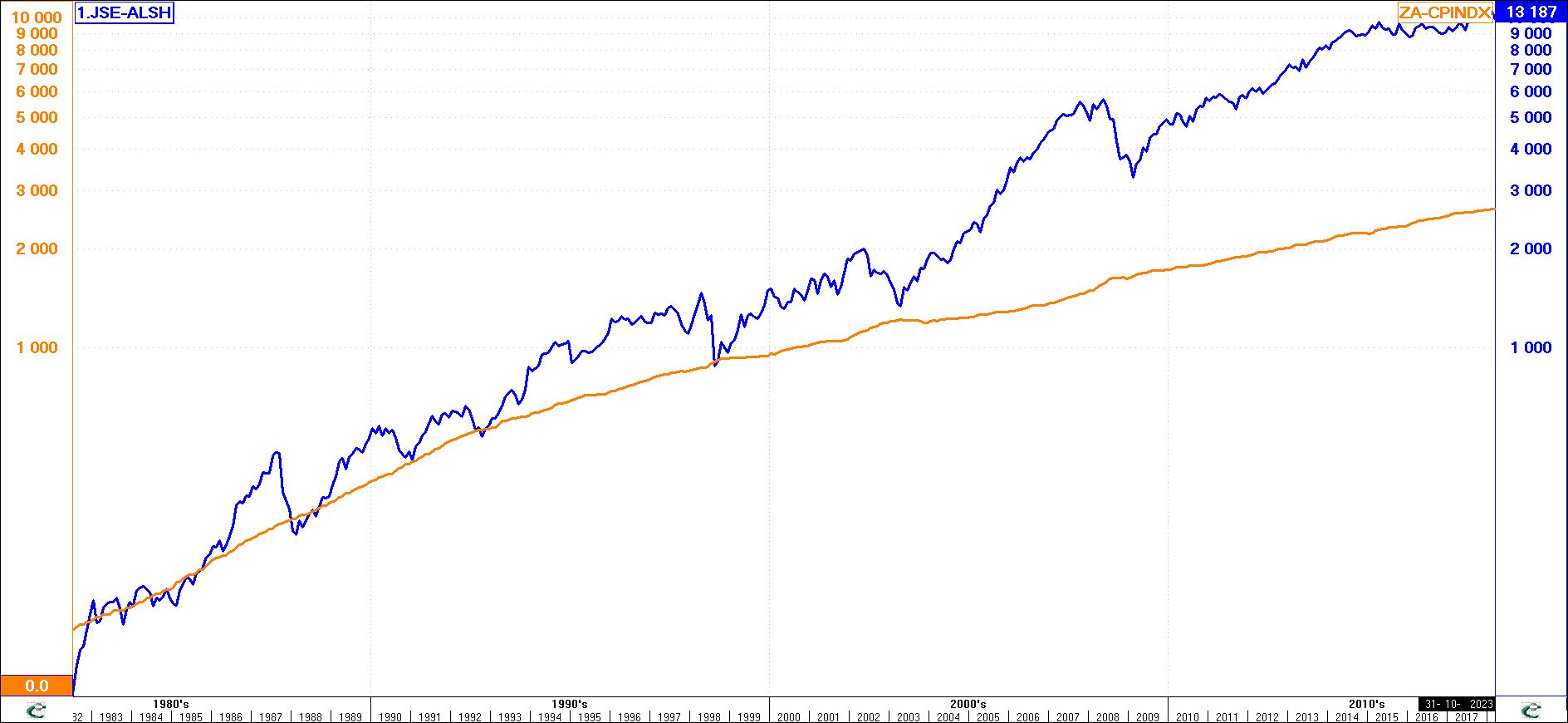

(click image to enlargen)

The purchasing power of money has declined considerably over the past 40 years.

Predicting what the next few years may hold is impossible, but there can be little doubt that in ten years’ time $100 will not buy as much as it does today owing to the effects of inflation.

Historically, goods which cost 1000 in January 1980, cost about 2750 40 years later at the end of 2010.

However, as this graph shows, $1000 invested on the Johannesburg Stock market at the same time, would now be worth over $10 000.

Other exchanges show similar or even better results.

Thus, investing in shares is one of the few ways of substantially beating inflation.

Clearly, the best way to invest your money is in shares listed on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange, as that investment has always out-performed other forms of investment in the long term.

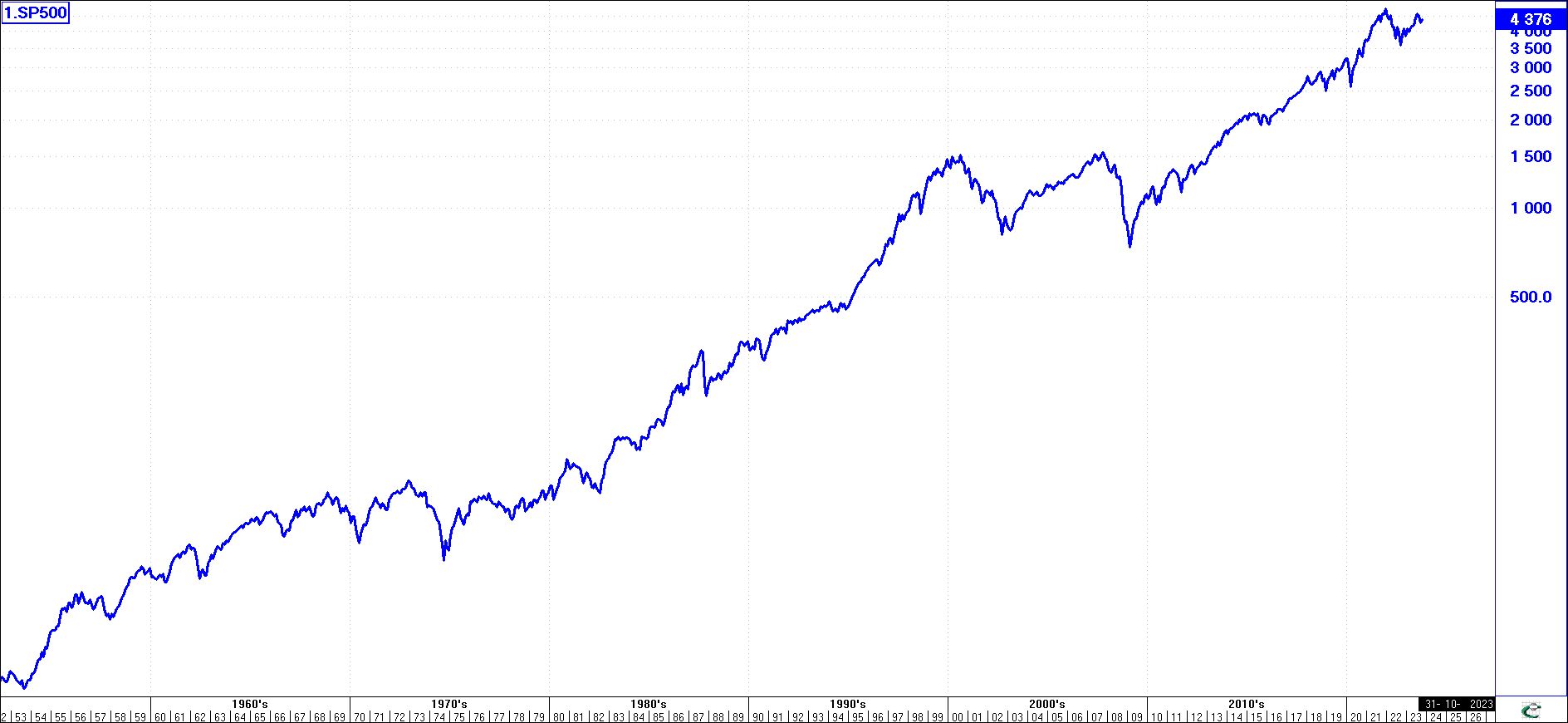

(click image to enlargen)

The market does not always go up however.

As you look closely at this graph of the S&P 500 index, you will see periods where it has effectively moved sideways for months, even years.

Consider the period starting in early 2000 until late 2010.

Having had money invested during that time period could have been rather disappointing although looking back now we can see that it was merely a

period of consolidation in the market which was followed by a strong Bull Trend (400% over next decade).

This helps us to understand that the timing of buying and selling shares is extremely important.

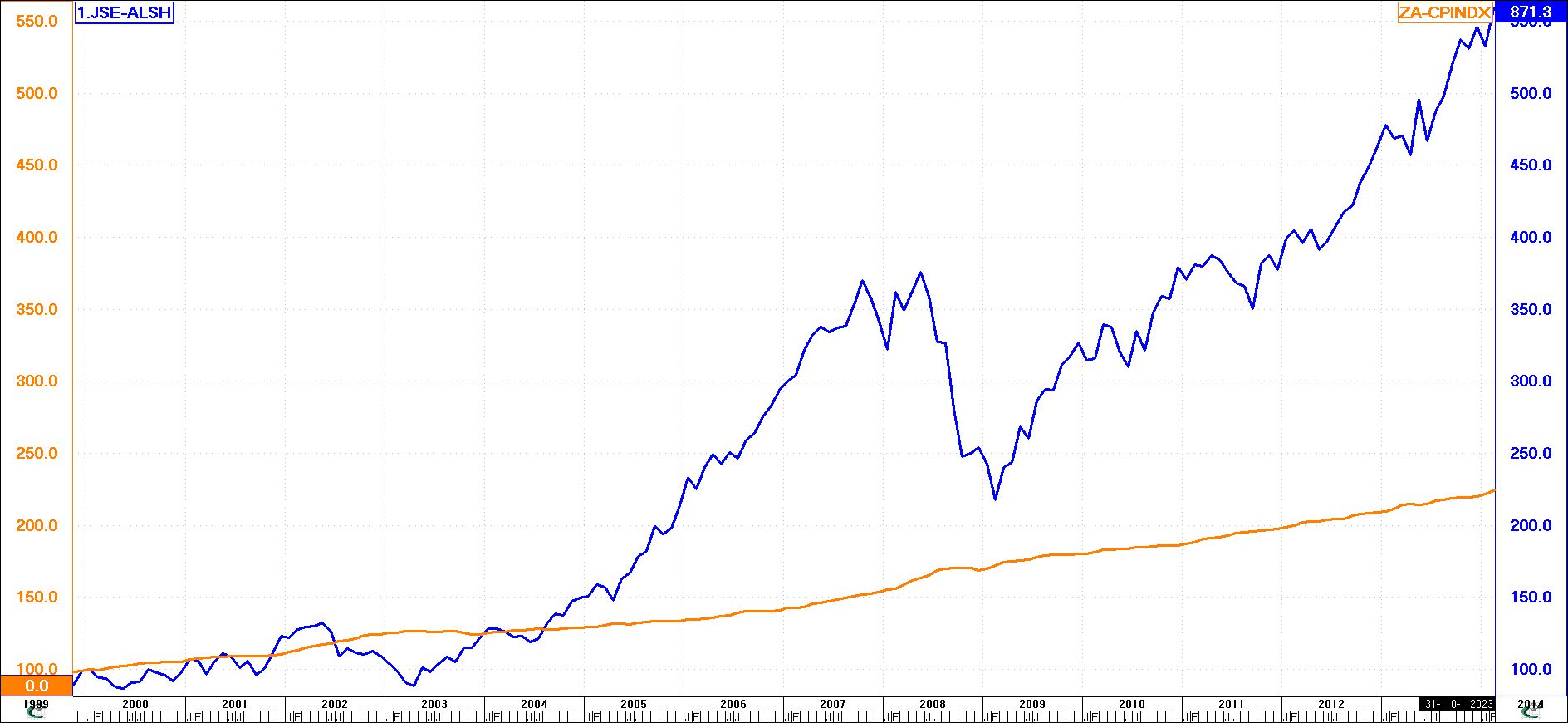

(click image to enlargen)

Looking at this graph we can also see that although in the long term the market has always outperformed inflation there are certain periods where this may not be true in the short term.

For instance during the initial time period spoken of in our previous graph (2000 to 2004), the market outperformed inflation part of the time and the dropped below inflation for the latter period.

However, after the period of consolidation it strongly outperformed inflation for the following decades.

Having established that the market performs well when compared with the inflation rate, bear in mind that individual shares on the stock market are not all good investments all of the time. Think for a moment of investors who bought Trust Bank at or near R10 and ultimately sold at 21c and those unfortunate folk who bought the property share Glen Anil for R32 and lost their entire investment when the company was liquidated. The one thread common to investors who suffered is ignorance - ignorance of how stock markets have behaved in the past in relation to the economic cycle; ignorance of the information to be derived from charts; ignorance of the importance of values; ignorance of investor psychology, etc.

In addition to companies that may go into liquidation or simply perform poorly due to bad management, the share market as a whole can be negatively affected by other factors. No country operates in a vacuum. If international markets plummet as a result of a failing American economy or an earthquake in the Middle East, the stock market in South Africa will go down. Despite no change in an individual South African companies profitability, its share price may plunge (or soar) because international or local investors have changed their sentiment.

The Stock Market thus has many risks that can counter the rewards of outstanding capital growth. To be a successful investor requires prudence, patience and planning. Before starting to invest, be sure of your motives! If you are in it to make a “quick buck”, you may loose a small fortune. Remember that if you do not invest wisely, you could lose a large percentage of your investment - can you afford to lose what you have invested ? If the market crashes or makes a large correction, can you afford to leave that money invested until the market recovers ? Do you have the discipline to only invest from your disposable income after you have covered all your other essential financial obligations ? If you cannot answer “YES” to all three of these questions, you probably will be one of those persons who walks away from the Stock Market convinced it is a place to lose money in, rather than a means to finance and benefit from a growing economy!

While EasySoft cannot guarantee that the knowledge derived from these pages will make you rich, we are convinced that with the right motives, by studying and applying the principles in this course, you will considerably improve your investment performance.

Before discussing all the different type of shares, a brief look at the history behind Stock Exchanges in general, will be of interest.

The Start of the Stock Exchange

Before stock exchanges existed shares were sold either by brokers, often in coffeehouses, or else by privately hired auctioneers.

The world's first joint-stock company (i.e - the Muscovy Company -) was founded in London in 1553. As the number of joint-stock companies grew, so did the number of brokers - acting as intermediaries for investors. In 1760 a group of 150 brokers formed a club at Jonathan's Coffee House in London where they met to buy and sell shares. In 1773, the members of this club voted to change the name of Jonathan's to the Stock Exchange and the London Stock Exchange shortly thereafter had its start.

The Exchange developed rapidly - playing a major role in financing UK companies during the Industrial Revolution. By the 19th century more than 20 stock exchanges were operating around the country. At first, these provincial exchanges operated independently from London, but the increasingly sophisticated market of the 20th century brought the need for amalgamation in 1973 into what we know today as the London Stock Exchange (LSE). The London Stock Exchange Group (LSEG) was formed in 2007 with the acquisition of the Italian exchange and stakes in other exchanges in the years following.

In America, the most important stock exchanges are the New York Stock Exchange and the American Stock Exchange, both in New York City; the Midwest Stock Exchange, in Chicago; and the Pacific Coast Stock Exchange, operating in San Francisco and Los Angeles.

The first formal Stock Exchange was started in Philadelphia, the nation's capital at the time, in 1791. The New York Stock Exchange, which some years later became the largest of all American exchanges, was organized in May 1792 by a group of 24 brokers. The other major Exchanges in the United States all had their beginnings in the 20th century.

The JSE’s History

South Africa’s connection with the stock exchange can be traced back to before the time of Jan Van Riebeeck. That historic voyage was based on the results of many earlier expeditions, all of which had been sponsored by European companies who in turn had raised capital from shareholders to do so.

On 2nd March 1602, the Dutch East Indian Company was founded in the Netherlands. With a vast share capital contributed by various merchant centres, it was the largest financial enterprise in the world. The expedition of Van Riebeeck contributed substantially to the fantastic returns achieved by the Dutch East India company. Clearly, without the mechanics of a stock exchange, the necessary funds would not have been raised to finance this venture, and South African history would have been vastly different.

The first specifically South African shares were recorded in 1801, of a nonprofit making nature, and were issued to 24 shareholders for the purpose of funding an amateur theatre.

A whaling company was set up in 1802, offering shares to the inhabitants of the Cape of Good Hope and in 1804 “The Kamer van Commercie” was founded by Governor Janssens to be replaced thirteen years later by the Cape Town Commercial Exchange. Trade in wool, wine, hides, ivory and other products flourished. In 1843 an insolvency ordinance ensured that these early companies had limited liabilities (even before England instituted such a law). In 1862 the original Companies Act was promulgated. Most of these companies were run with reasonable efficiency and their returns were most satisfactory.

In 1861, the Governor of the Cape, Sir Philip Wodehouse, signed “an act to limit the liability of members of certain stock companies”. It laid down elaborate details about official returns and the transfer of shares. Although it did not fulfill all the hopes of its proponents, it marked the country’s entrance into the world of modern finance and business. A year later a similar act was drafted in Natal, where several institutions had made their appearance and even the Orange Free State on a more limited scale, saw the formation of some companies and the issuing of shares.

From the early 1850's, many companies were set up in the Transvaal. Although not successful in a business sense, they were instrumental in familiarising the public at large with the concept of joint stock companies. With the discovery of diamonds, the next big development occurred in Kimberley. By the beginning of the 80's, the days of individual diggers, along with canvas houses and tents, ended. Mining and businessmen established an institution that was to be the first of its kind in the country - the Kimberley Share Exchange Broking and General Agency Company Limited.

In 1887, the Johannesburg Stock Exchange opened its doors. At this time, many other exchanges were in existence. With the establishment of De Beers Consolidated Mines in 1888, the number of companies listed on the Kimberley exchange fell to an unprofitable level. In 1894, this exchange was closed. The same fate was to be suffered by a dozen other smaller exchanges that had sprung up all over the country. Some of them were in existence until well into the 20th century (ie.Pretoria Exchange). However, by the 1920's all of them had closed. The Johannesburg Stock Exchange became the economic powerhouse of Southern Africa.

It was Benjamin Woollan who founded the JSE at Ferreira’s Camp in 1887. In 1890 the second JSE building was established in Simmonds Street. Due to space constraints, trading activities at these premises expanded into the street which was then chained off, hence the phrase “to trade between the chains”.

In 1933 the Open Call exchange (later called the Union Stock Exchange) was opened in Johannesburg. However, in 1958 the government closed this exchange and transferred all its listed companies to the JSE. Since then, this has been South Africa’s one and only stock exchange.

The next major change in the JSE occurred in 1996 when it moved from the old “Open outcry floor trading” system that had been in use since inception to that of a completely computer terminal based electronic trading system (JET - Johannesburg Electronic Trading system).

In July 1999 the JSE introduced the STRATE. The Share TRAnsactions Totally Electronic (STRATE) is a new electronic settlement system for transactions which take place on the Johannesburg Stock Exchange (JSE) and off-market trades. It will bring South Africa in line with international practice and enhance the security of settlement in the equities market.

The STRATE initiative will mean that there will no longer be any physical equity script in a Central Securities Depository (CSD). This is no different to the money you have in the bank, as all records of your deposits and withdrawals and current balance are held electronically and have been for decades. This de-materialisation of script facilitates settlement and the transfer of ownership by electronic book entry. This is now the norm in all exchanges arround the world.

What Are Stocks and Shares?

A share, as the word implies, gives the owner a part of the company. You thus share in both the profits and the risks of this company. Owning shares in a company means that you own part of the premises, machinery, furniture, stock, etc. If a company has 5 million shares in total and you own 100,000, this means that you own 2% of this company (since 100,000 is 2% of 5 million). Another name for shares is Equities, meaning the owner has equal rights with all other shareholders - limited of course, to the size of the shareholding.

The JSE notes that whether your holding is known as stock or shares, it is evidence of your part ownership in a joint stock company. Few people today know or care which company has stock and which has shares as they are all traded in the same way. Neither is the par value (or basic value) of a share of much interest as the prices that are quoted daily are determined by supply, demand, and the trading performance of the company concerned.

Today the term stocks is most often used to refer to units of investment in the gilt market, units of Government loan stock, municipal bonds and the loans raised by utilities like Eskom, Transnet, Umgeni Water Board etc. These are also known as Gilts as in “gilt-edged” stocks because of their value and security. To add to the confusion a popular name for Gilts is Bonds. One often sees reference to the Bond Market in the financial press.

Shares are also called Counters and Securities - although this is a broad term that includes debentures, gilts and other forms of tradeable paper.

Ordinary Shares

Ordinary shares (the most common form of listed shares) entitle the owner to a share in the profits of the company. Twice a year (some companies do so only once a year), the management of the company will issue a report on its progress over the preceding 6 months (or year). If the company has achieved a profit (after all the expenses have been paid), the management may decide to pay a portion out to shareholders. This is known as a dividend.

A dividend is an amount paid out to a shareholder. Usually the company will not pay out all of the profits as dividends as some profits may need to be retained in the company for the further development and expansion of the business. If the company is liquidated, then the assets of the business are sold. The proceeds are distributed first to creditors, secondly to preference shareholders and lastly to ordinary shareholders. Thus in the event of liquidation, ordinary shareholders are likely to suffer the most as they are the last to be paid out.

If for a given year the company does not make sufficient profit to pay a dividend, then both ordinary and preference shareholders will not receive any payout. If a company does not pay a dividend, it is known as “Passing” a dividend.

As an ordinary shareholder, you have the right to receive dividends paid out by the company once or twice a year. You can attend the general meetings of the company and ask management questions. By law you must receive the annual (and six monthly) financial reports from the company. If due to any reason the company sells its assets (ie. it is liquidated), you are entitled to your shareholding equivalent once creditors and preference shareholders have been paid out.

Anyone wishing to take control of a company by acquiring a large block of its shares, must first find a willing seller and then offer them a price above that normally quoted on the JSE (though not necessarily). To be the controlling shareholder in a company, one must expect to pay a premium for that right.

Owners of Ordinary shares have a right to vote on major company decisions. The weighting of their vote is based on the percentage holding of company shares which they have. Sometimes a company will issue non-voting ordinary shares which are usually called “A” or “B” shares. Companies sometimes also have “N” shares (not to be confused with NPL’s or Nil Paid Letters!) which although they have voting rights, are usually only a small percentage of that of ordinary shares (ie. you may need 100 000 or more “N” shares to equal the vote of just 1 000 ordinary shares).

Preference and fixed interest shares

Preference shares or “Prefs” as they are more commonly known (usually denoted by a “P” suffix in the newspaper share listing), entitle the holder to a participation in the profits of a company before the declaration of any dividend, and should the company be wound up, they usually also have a prior claim on the assets after creditors have been satisfied. It may happen that only the Pref shareholders receive a dividend.

The dividend paid on pref shares is not decided by management (as with ordinary shares) but is a fixed percentage of the original price at which the pref was issued to the holder. For example, the Prefs of a particular company were originally issued two years ago at 1000 cents each offering a fixed 15% dividend a year. This means that the company will pay a dividend of 150 cents a share (usually split into two 6-monthly payments of 75 cents each).

Most stock market investors will not buy Pref shares as although they hold no great risks, they equally hold no major growth potential. Like gilts, they are a safer investment in times of national and international economic stress. However, they usually face the same drawbacks as do gilts, in that, because their interest rate is normally pegged at a fixed rate, their value tends to decline at times when the general structure of interest rates is rising. Preference share owners have no voting rights.

-

Fixed Interest Shares

The term is self-explanatory. The interest (or dividend) paid is at a fixed annual rate and is not changed.

-

Cumulative Preference Shares

Cumulative preference shares are identical to normal preference shares, unless the company makes a loss for a number of years and is unable to pay any dividends. In such instances each missed dividend that should have been paid out is “accumulated” until the company can pay them.

-

Redeemable Preference Shares

Redeemable preference shares means that the company undertakes to pay back the full amount of the shares (ie. “redeem”) to the shareholder at some fixed future date.

-

Participating Preference Shares

These shares are more attractive than normal preference shares as they offer a higher dividend if the company does well. They are a combination of preference and ordinary shares. Besides entitling the owner to the fixed payable dividend of a Preference Share, they also pay a percentage (usually 10% to 15% of the ordinary dividend) of the profits of the company. A variation is that the participation in the profits may only occur when the ordinary dividends reach a certain level. A typical example could be the company paying out a 5 cents per share profit (in addition to the fixed dividend) if the ordinary dividend exceeds 35 cents a share.

-

Convertible Preference Shares

These are normal preference shares which offer the option of converting them to ordinary shares at some future date.

Debentures

These are not shares (although you buy and sell them in the same way), but long term loans that have been raised through the JSE. They are also known as “Loan Stocks”. Debentures (usually denoted by a “D” suffix in the newspaper listing), are usually issued in units of R100 each and pay a fixed interest rate despite the companies profit situation. In effect you are lending money to the company and thus debentures are reflected as long-term loans in the company’s balance sheet. If the company is liquidated, debenture holders are among the first to be paid out.

Convertible Debentures

(usually denoted by a “CD” suffix in the newspaper share listing) are identical to Debentures, except that they can be converted to ordinary shares at some future date.

Warrants

A relative newcomer to the market is the Warrants sector. They have proved to be very popular with individual investors because in their first year of listing on the JSE, just on a billion warrants were sold.

A warrant is essentially a contract between its holder and the issuer of the warrant. This contract is an agreement in which a specific share will be bought (known as a call) or sold (put) on or before a specified date (final exercise date) at a set price (exercise price) against payment of a premium which is the market price of the warrant. When you buy a warrant, you buy the right - but not the obligation - to buy or sell a share, or a prescribed basket of shares, or an index, at a given price known as the strike.

The price of the warrant is listed in cents as in the case of a normal share and normal brokerage charges apply.

A warrant is traded in a specific cover ratio, for example, one warrant can be exercisable into one share or ten to one or even one hundred to one. Warrants are speculative and therefore although high returns are possible the risk is high.

Example: DB 1FSR 1000c Mar01 (Trading at 25 cents)

This is a call on FirstRand issued by Deutsche Bank (warrant underwriters) to buy FirstRand shares at 1 000c a share in March 2001.

If you buy 10 000 warrants at the then current price of 205, for about 20,900 you will be able to exercise your right to buy 10 000 FirstRand shares on or before March 8, 2001 at 1000c a share.

To make a profit, if you hold to the final exercise date, FirstRand shares should be at least 1000c + 209c = 1 209c by that date. The current price is 680c, so to make a profit, the share must rise in the next two years to 1 209c.

Because of the gearing involved it is also possible to make a good return on the investment in the interim.

When the price of FirstRand goes up the price of the warrant will follow. The rise or fall of the warrant won’t, in most instances, be proportional to the change in price of the underlying share.

Similar rules apply to put warrants. The difference is that you are buying the warrants to sell the underlying shares to the issuer at a predetermined price. This type of warrant is for those expecting the market to fall.

Unit Trusts / Mutual Funds

Unit Trusts or Mutual Funds are investments that enable you to pool your funds with other investors. These funds are made up of investments in a range of shares quoted on the local (and perhaps international) exchange and are coordinated by experienced investment managers. Unit trust companies normally ensure that these managers have a wealth of experience and a well documented investment performance record. An investor is allocated a number of units at the time of their investment. Those units represent their share of the overall fund. This makes it possible for you to invest in markets which you would normally have had difficulty in accessing as well as sharing in the rewards of the exchange without running the risks of direct investment.

Most Unit Trust companies offer a range of different unit trusts (funds) each having a different focus in the market. The benefit of having a range of different funds is that you are able to choose a unit trust that suits your risk/ return requirements, market conditions and personal circumstances. If you consider Coronation Unit Trusts as an example, there are about twelve different funds to choose from within the family of funds. Two of these are the High Growth Fund and the Balanced Fund.

| • |

Coronation High Growth Fund -

This fund has as its long term objective capital growth and income is merely a secondary consideration.

The fund will thus be invested in carefully researched, fundamentally sound high growth companies listed on the JSE.

Vigorous selection criteria will be used to identify specially niched investment opportunities with the intention of producing above average returns over a period of time.

This fund is therefore ideal for an investor who is looking for a diversified, high growth equity portfolio.

|

| |

| • |

Coronation Balanced Fund -

The Balanced fund is managed according to the prudential investment requirements which govern the management of pension and provident funds.

The underlying investment of the funds will comprise a balanced spread of equities, bonds and cash.

The aim of the fund is to ensure an optimum mix of security, return and growth.

This is intended to suit the investor who is in search of stable, inflation beating capital growth with a reasonable level of income and who prefers a lower level of risk.

|

When investing in unit trusts you can either invest a lump sum of money or make regular monthly investments. When investing a lump sum it usually has to be an amount in excess of about R5000. Your entire investment will thus immediately benefit from the growth and income potential of the unit trust that you have chosen. An investment of a fixed amount on a monthly basis is an attractive way to build up capital. It gives you the benefit of rand-cost averaging which means that if the unit price falls, your monthly investment buys more units and when the price improves, the value of your overall investment will increase. You can normally arrange to have the amount of your monthly contribution automatically increase each year or even discontinue your contributions and still retain the units already purchased. The minimum monthly contribution is usually about R500.

It is generally recommended that you hold unit trusts for at least three to five years. In so doing you will reap the full benefit of the investment. You may wish to periodically switch your money between funds within a family of funds to ensure that you are getting the optimum investment mix. This can be done very economically as long as you keep within the same family of funds.

The fact that unit trusts are made up from pooled resources means that a portfolio manager is able to access lower transaction charges than individual investors which of course implies that they represent good value. There is a compulsory charge comprised of marketable securities tax, stamp duty and brokerage. There may also be an initial charge of up to 5% and an annual management fee of 1% of the market value of the portfolio.

When income is received from dividend payouts or the like you can be paid these directly into a nominated bank account or reinvest it so as to enlarge your unit holding. Such payment or reinvestment will normally take place at the end of March and September and will take place on the first working day after the distribution.

How do you buy Shares?

You can buy shares by going to your bank. You would speak with an investment consultant and they would then do the necessary transactions on your behalf. However, most investors usually go direct to a stock broker. This usually results in you being able to buy and sell shares quicker and at lower commission rates than through a bank. There are also many options of online brokers where there is no human interaction. This results usually in quicker execution and lower commissions.

What Stock Broker do you choose? Unfortunately it follows much the same route as choosing a good doctor, lawyer, or similar professional. Ask those who have had dealing with stock brokers, which one(s) they have found good. Shop around a number of brokers and find out what their charges are. As mentioned earlier in this section, the commission stock brokers charge varies and some will inflate their charges to discourage having to deal with the “small investor”. Thus many small investors will go the online broker route.

What defines a small investor varies from broker to broker. While some brokers will be happy to buy just a few hundred rands/dollars of shares for a client, others may want you to arrive with a million or more in your bank account.

Different brokers focus on different sectors of the market (i.e. mining, financial or industrial shares), while others are happy to deal in any share. Some will offer in-depth research and consultation (maybe at a higher brokerage rate) while others provide a “no-frills” service at low brokerage rates.

As you will learn, in addition to the Share Market, there is also a Gilts, Warrants, Bonds and Futures Market that you may decide to invest in. Some brokers may not deal directly in all of these markets.

Thus the stock broker for you is the one that understands your personal needs and “speaks your language”. The stock broker that’s right for you depends totally on what you require. You may even find that your needs are best served by utilising more than just one broker!

What type of Share to Buy?

Most investors will simply go for ordinary shares. Although they carry a greater element of risk, they also have the greatest prospect for making a substantial profit. Clearly a certain amount of work is needed to select good quality shares in which to invest.

Some investors may feel that they will play it safe by simply buying “Blue-Chip” (the ordinary variety thereof) shares. “Blue-Chip” shares often have a number of listed subsidiary companies. Obviously not all these subsidiaries will perform equally well. Additionally, when some are performing well, others may be doing badly. The profitability of the main holding company will be the average of it’s subsidiaries. If one or more of them performs badly, this may unduly reduce the perceived profitability of the entire holding company. If an investor is prepared to take the time, he will often find it more profitable to invest in on or two of the more successful subsidiaries, rather than the holding company.

To prosper on the market, all that is necessary is to decide what stage of the economic cycle the market as a whole, or a sector in particular, is at, at any particular moment (discussed in Lesson 2). This is not as simple as it sounds because of the many factors involved, for example, monetary, political, economic, technical and unforeseen calamities.

Over the years many different methods of studying these market variables have been devised, some of which are more effective than others. Usually, these methods of market study may be divided into two main categories, namely Fundamental and Technical analysis.

Fundamental Analysis

Fundamentals refer to the underlying factors that affect the value of a share. The Economic, Political and Monetary situation of the country (and/or the International scene) influences shares as follows:

Economic - If the economy is in a recession, share prices usually decline. During good times they generally rise.

Political - Political instability causes a lack of confidence and results in share prices falling. During stable political times, shares will generally increase.

Monetary - Declining interest rates means that more money comes into the market as individuals realise that there is a better return to be had in equities than in a savings account. In such times, shares increase in price. Conversely, when the rates move upwards, money moves out of the market and shares fall. Interest rates, in turn, depend on such factors as inflation, sanctions (when they existed) and money supply.

Besides these general effects on the market as a whole, individual companies are affected by their own performance. The company’s performance can be judged by its earnings, the dividends paid, the net asset value, the debt/equity ratio (all the information which companies normally provide in their annual reports).

Fundamental analysis is used to determine whether the current price of the share reflects “good” (or “poor”) value, and thus will increase (or decrease) in the future.

Technical Analysis

Technical Analysis involves studying the price (and/or volume) movements of the share in isolation. As the price is a direct reflection of how the market perceives the value of a company, technical analysts’s believe that all the fundamental information has already been factored into the chart movements.

In addition, technical analysis can also involve the graphing of indicators or formulas that are applied to the share price and/or volume to filter out minor moves and highlight the major trends.

Technical Analysts look for patterns and their repetition. They note the levels and subsequent market moves. When they identify a similar pattern/performance they then expect the market to react in the same way it has previously done.

The popularity of technical analysis has surged dramatically with the development of various software programs that enable the investor with a computer to compete on more than even terms with the experts.

Fundamental or Technical - Which is Better?

Fundamental analysis can help you in determining if a share is a good investment, however it cannot help you correctly time your buy and sell decisions.

Technical analysis can help you to accurately time your entry into or exit from a share, but it cannot tell you anything about the long-term value of that share.

Thus, fundamental analysis can be used in isolation for long term investments and technical analysis in isolation for short term trading with a fair measure of success. However, the wise trader and/or investor will combine both these approaches to optimise his trading/investment results.

Where to Go for Stock Market Information

The Company report will give you a balance sheet of the company, along with the income statement, etc. It will also include a statement by the chairman covering the general performance of the company over the previous year and any major acquisitions or changes in operations. You can probably obtain all the fundamental information you require from the Company Report.

A Business Focussed Daily is a daily newspaper which in the past was indispensable for the serious investor. This daily morning paper carried not only financial news specific to companies listed on the local exchange (including the publishing of all Company Notices), but also publishes general economic news of both the local and international markets. It would also publish a complete list of all shares trading on the local exchange (the UK Financial Times would be a good example).

Many daily (and weekend) papers may have a Business Report and share page with limited company/economic news.

There are also many and weekly/monthly/quarterly publications that provide similar material.

General Radio & Television often carry a stock market report each week day evening and quote some closing price of all stocks that traded that day. They may also give a local and international view of the market with relevant interviews.

Financial Radio & Television have proliferated and they devote their entire broadcast to the market

The Internet - is with out doubt the current ‘go-to’ source of financial information. You can easily link up with various news groups or web pages both locally and internationally that give out financial information. For instance, it is possible to read The Wall Street Journal and The London Financial Times online. The major internet data providers all have entire websites devoted to market related information ( https://finance.yahoo.com/ - https://edition.cnn.com/business - https://www.msn.com/en-us/money - https://www.google.com/finance/?hl=en - etc.) And usually provide solid factual information. Obviously on the Internet there are many website and YouTube channels that may promote ‘information’ for their own advantage, rather than yours!

Your Stockbroker can also give you his view on the shares that you are considering buying.

Understanding Your Newspaper or Internet Share Page

These vital sources of information usually cover all daily transactions on one or more Exchanges. First though, one must understand what is meant by “the index” or indices.

For a given exchange, The Indices represent the average performance of a particular group of shares (ie. a market sector). For example, the JSE Gold index is an indication of how the main gold shares have performed on average. The index is calculated by “weighting” the shares in the sector. This weighting is decided on by the devisors of that Index Series.

Throughout the day, the Exchanges computer calculates the value of the indices by multiplying each share in the index by its weighting and then adding up all these values. The result is the Index for that sector.

In some sectors, the movement of the index is influenced by just one or two shares. In other sectors, there are so many large companies that make up the index that no one single share dominates the index.

For example, the JSE All-Share index is the movement of all the shares (all the important ones) on the JSE. As it is the average movement, some shares will have moved more, some less.

By looking at the Index, you can get a good idea of what the market overall has done. For the UK markets, the FT-100 Index (Financial Times) is used. In New York the Dow Jones Industrial (30 stocks unweighted) is used. The Standard and Poor (SP500) uses a base of 500 shares and because of its broader base is often used as a more representative indication of what is happening on the American stock market. The ASX-100 and ASX-200 are popular indicators of the movement in the Australian market.

In addition to listing many local and international Indices, the share pages (printed or via the Internet) will also list details of the individual shares. As the prices of the individual shares fluctuate (and hence need to be regularly checked), it is also obvious that the buying and selling of them requires precise timing.

There is considerable information displayed on the share page. A correct understanding of the various values and how their movement affects a shares worth is needed.

Next to the name of the share, you may get the code used to reference the stock. In this example the UK bank Barclays has the stock exchange code ‘BARC’ and the ‘.L’ indicates it is on the LSE exchange. The data displayed is not live, but delayed (usually from 5 to 15 minutes - exchange dependant). The values are in British Pounds (GBP - 0.01 - pences). Thus the stock is trading at 153 pence (GBP1.53). It is trading lower that what it closed at the previous day by about 4 pence (-3.98 pence or -0.0398 Pounds) and this is about 2.5% lower. If it was currently trading higher that the price at which it closed previously (i.e. yesterday) the numbers would be ‘+’ and coloured green!

The above is the main information you will see if just looking at the heading or if looking at a list of items. You will probably also see some of the following (or be able to click on an item to select detailed information of just it).

-

Previous Close or Ruling Price equal to the price at which the last transaction of the day was concluded

-

Bid / Buy the highest price investors are prepared to pay for a share. It may often change during the day.

-

Ask / Sell the lowest price that an investor is willing to sell his shares for.

-

High the highest price the share traded at during the day.

-

Low the lowest price the share traded at during the day.

-

Day’s Range the High and Low of the day. You may also be shown the week/month or year range.

-

Open the price at which the first sale of the day is made at. If no trades have been made it may show the Previous Close value.

-

Volume the number of shares that have changed hands today.

-

Avg. Volume the average number of shares that changed hands on a given day.

-

DM - DAILY MOVE the difference between the previous day’s price and that of today. Sometimes this move is also represented as a percentage (DM%).

-

WM% - WEEKLY MOVE % the percentage move over the last week.

You will also find a description of these and other items in the Glossary. Below is a detailed discussion of three importat data items you may wish to consider.

Understading Price Earnings Ratio (PE Ratio)

This is an indication of the value of the share. It tells you how many years it will take the company to earn (in profit) the current cost of the share. It is calculated by dividing the share price in cents by the after tax earnings per share, in cents. For example, let us say the price of a share is currently 500 cents and the earnings per share were 25 cents in the last financial year. The PE ratio tells you what kind of value you are getting should you decide to buy the shares and as such can be a valuable indicator (or completely misleading - the smart investor can tell the difference).

Using PE’s in isolation can be misleading since other important factors such as the quality of management, the relationship between share price and net asset value, and the industry’s local and international prospects, cannot be ignored.

A rule of thumb is that a share with a PE ratio higher than 25 is expensive from the perspective of historical earnings, while one with a PE lower than five could (if the other factors are right) be a bargain. A high PE implies that investors are prepared to for more years of future earnings and/or that they expect the company concerned to show substantial profit growth. In reality though it could be that the share is simply overrated and that investors are prepared to pay too much for it.

Essentially, the PE ratio measures the present value of future cash flow, relative to the previous year’s earnings. As such, PE usually reflects the market’s expectations of a company’s growth. A high PE could imply high growth, but in some cases - such as certain companies in the electronics sector - PE’s reach such heights that many investors might consider the share overpriced and unlikely to yield returns to justify the investment.

In 1996, Dimension Data, for example had a PE of 60, against a sector average of 16. With its then 65% earnings growth, it was keeping pace with the market’s expectations, but still, such an exceptionally high PE ratio spelt caution.

A high PE may also be an indication that a stock is fully priced and that a price correction could be due. In any case, as the PE rises it becomes increasingly difficult for the stock to live up to expectations.

When a company goes through a growth phase, it tends to start with a relatively low PE. During the period of growth the PE rises, before dropping again as growth tails off.

Slackening in growth could indicate the company’s management has lost its competitive edge, or that the market is saturated, or it could merely indicate consolidation prior to further growth. The challenge is to understand both the individual company and its industry well enough to take an educated bet on its future prospects.

What the investor should look for is companies like Dimension Data at the start of their climb. However, the typical private investor is inclined to buy high and sell low - or, if a bargain hunter, to assume a low PE automatically means good value.

However, there could be good reason for a low rating. Sappi in 1996 was no bargain with a PE of 5,6, thanks to its high debt burden, low international paper prices and poor industry prospects.

And while a high PE could indicate a successful company with superb potential, in an imperfect market it can also belong to a stock running more on sentiment than solid prospects. It could indicate a company whose performance is collapsing so fast the numbers are distorted (CASHBUILD, with a PE of 88 in 1996 is a good example - Its PE rose because in the early days of the RDP its prospects seemed good, but when the RDP failed to take off and the company brought in some poor results, market confidence in the stock dropped).

But even with a dramatic down rating of the price of the share, relative to very low earnings the PE can still seem to have risen. When a stock is perceived as having good future growth prospects, the market allocates a premium, over and above its net asset value, to the value of the share. When it makes a loss, the market takes the premium away, and if it considers the loss sustainable it could rate the share at less than the company’s net asset value. For example, at one stage the clothing industry was rated at about half the value of its machinery.

Understanding Earnings Yield (EY)

This is an indication of the profits a company has earned compared with its share price. It is calculated by dividing the last declared earnings per share in cents by the current share price (also in cents), and expressing the result as a percentage.

If a share has an earnings yield of 2%, this means that the earnings or net profit of the company is only 2% of the share price. It could mean that the share is so highly sought after that investors are prepared to pay as much as 50 times the earnings of the share, obviously in anticipation of a strong improvement in earnings over the next few years.

Often a low earnings yield means that the company is just not that profitable. In general, you will note that the average company produces an earnings yield of between 10% and 15%.

Where the earnings yield is very high, it may mean that investors are not willing to pay much for the share (and thus its share price is low) although its earnings are good - in such a situation, investors believe that the earnings will not be maintained at the current level and will drop over the next few years (as will the earnings yield).

The Earnings Yield will rise if there is a drop in the share price or if there is a rise in the earnings per share. Conversely, it falls when the share price rises or the earnings per share drops.

Normally during the years the earnings yield will move in a historically set range. With a good company, during the year the earnings yield falls as the companies share price increases. The company then produces good earnings (better than last year). Now with the higher share price, combined with the higher earnings, the earnings yield immediately rises to somewhere near its original level. Since the company has again done well, its shares are now in greater demand and so the share price again rises (and the earnings yield falls). Investors will note any large move outside this range as an opportunity to invest or take profits.

Understanding Dividend Yield (DY)

This, as discussed earlier, companies usually only distribute part of the earnings as a dividend payout to its shareholders. This dividend, expressed as a percentage of the share price is the dividend yield.

The calculation of dividend yield is the same as that of earnings yield (dividing the dividend per share in cents by the current share price) and the same logic regarding its movement also applies.

In this lecture, the concept of a stock exchange has been explained. The basic information one needs to watch (and where to find it) on a daily/weekly basis, in order to keep track of shares one owns or hopes to buy, has been covered.

Finally, now that you know how the stock market works, the next question on your mind is likely, “what is the magic formula to make money?” Well its not necessarily a case of the effort that you put in being proportional to the amount that you get out of the market. There are tools that have been designed to make these choices and decisions easier for you to make. Your attitude toward your investments though is really what can make the difference as to wether they are successful or not. The following quotation overheard in conversation emphasises this for us. “The philosophy of the rich versus the philosophy of the poor is this: the rich invest their money and spend what is left, the poor spend their money and invest what is left.”

Once you have thought about that, you will probably start wondering about how you can practically determine which shares are the ones you want to own? The process of determining which shares are good shares, and which ones to avoid can be achieved by using “Fundamental Analysis”.

Fundamental Analysis will assist you to select shares. It cannot accurately help you time your purchase or sale of these shares. Timing is achieved by using Technical Analysis. However, before you can time a share transaction, you must first select the share.

Fundamental Analysis uses the information contained in the companies balance sheet and the analysis of the relevant items is discussed in

Lesson 2.

(You can also obtain this Lesson as a PDF document from our Services Menu, or click here)